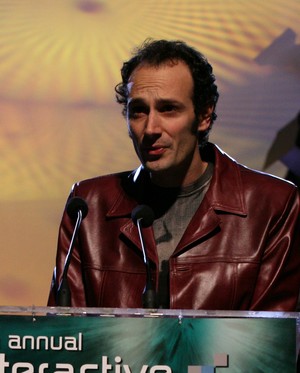

Alex Rigopulos is a member of the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences. He spoke at the D.I.C.E. Summit® in 2007. He works for Harmonix.

Alex Rigopulos is a member of the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences. He spoke at the D.I.C.E. Summit® in 2007. He works for Harmonix.

Q: How do you measure success?

A: A successful life is one lived joyfully.

Q: How do you want to be remembered?

A: That depends—who's doing the remembering? My sons? Friends and co-workers? Assuming you mean "remembered by history" (or whatever the appropriately self-aggrandizing term would be), at this point the easy answer would be that I want to be remembered as part of the team at Harmonix that changed the way people experience music, since that's been my life's work to date and presumably will continue to be for some time. But on the other hand, it's more fun to imagine that I’ll be remembered for something that I'll do in the distant future and haven't even thought of trying yet.

Q: On a practical basis, what's the one thing you're going to tackle next?

A: Making sure the Beatles game fulfills its potential.

Q: What's your favorite part of game development?

A: There are two points in the cycle of game development that stand out as my favorites:

First, there's the moment early on when the "first playable" comes together in reasonably coherent form, the moment where you see imagination having been turned into the first stroke of reality. When I had that experience with the Beatles game, I was literally trembling.

Second, there's the period shortly after the release of the finished game, when you've just flung your creation out into the world, and the first echoes start flowing back in. It's a period of great anticipation, anxiety, and – when things go well – gratification that the preceding year's hard labor has mattered.

Q: What game are you most jealous of?

A: Honestly, I don't think I've ever felt "jealous" about another game. When I come across another game that delivers something really beautiful or insightful or surprising, I don't feel disappointment, like "I wish I had thought of that." Rather, I feel inspired; it's a welcome reminder that there is still a lot of discovery ahead of me.

Q: What's the one problem of game development you wish you could instantly solve?

A: Getting from first inspiration for a game to vertical slice (fully polished prototype) takes far too long. I wish I could reduce this process from "months" to "days." (I expect that this problem will be solved right around the same time we get those flying cars we've been promised.)

Q: Tell us one of your recent professional insights.

A: I try not to have professional insights.

Okay, that's kind of a wise-ass thing to say, but businesspeople have a tendency to "have professional insights" and then reduce said insights to some pithy nuggets of knowledge along the lines of "the way the world works is X." Well, in my experience, the way the world works may or may not be X, depending upon context and a whole host of subtly interconnected variables, so I find these sorts of observations/guidelines to be wrong (i.e. misapplied) approximately as often as they're right.

(Wait...was that a professional insight?)

Q: Are games important?

A: It's funny to me that this question is even asked. Games entertain us, and they do so in some special ways that other media can't. So asking this question is, to me, tantamount to asking: Is entertainment important? Perhaps not as important as, say, healing the sick or feeding the hungry. But entertainment is a vital element of the texture of life. Living would be much, much emptier without it.

Q: Do you think it’s important for developers to continue playing games?

A: That depends on what sorts of games those developers intend to develop. If a developer is working within a well established genre and attempting to advance that genre, it's more or less indispensable that the developer know their turf intimately. (It's also important to study other game genres for applicable lessons and cross-pollination.)

But some wonderful discontinuities in game development have come from people with little or no experience in playing the established canon. Think of the original Parappa, or more recently, Katamari Damacy. Games like these come out of nowhere, and they're possible, I think, because their creators are unencumbered by a lot of preconceptions about what games are supposed to be.

Q: What's the biggest challenge you see facing the industry?

A: I don't actually see any one conspicuous Biggest Challenge Facing the Industry. Rather, all of the usual suspects are at play, e.g.: Development costs are rising, arguably much faster than the market size is growing. And now, as a special bonus challenge, this trend is set against an awful general economic climate, wherein it's harder for publishers to charge full price for games. And as in most entertainment businesses, there's an over-supply of content, which creates a lot of noise and raises the cost and challenge of marketing games – even very good ones. No surprises here.

But I tend to be an optimist about these kinds of challenges. The consumer appetite to be entertained is not going anywhere. And the industry has plenty of smart, creative and passionate people; they will adapt. (There are already some enormous new opportunities, such as the arrival of digital distribution onto the consoles.)